(Editor’s note: This is part two of a two-part series on the emergence of local grains and freshly milled flours. Check out part one here.)

Reinventing America’s grain milling process and supply-chain infrastructure is a powerful goal for innovators like Cairnspring Mills. Opened in June 2017, this new grain mill in Burlington, Washington, specializes in European-style bread flours that contain more wheat bran and germ for deeper flavor, such as Yecora Rojo Type 85 and Organic Expresso — each designated by the variety of wheat.

As the movement of local bakeries milling their own flour continues to grow, the next step — the regional mill — is beginning to take shape. George DePasquale, co-founder of Seattle wholesaler The Essential Baking Company, a customer of Cairnsping, recalls participating in flavor panels when Cairnspring was testing various bread flours prior to opening.

“Those were great sessions,” DePasquale says. “When six or eight people were coming up with the same verbiage, then you know you’re on to something. As we get our bread onto the chefs’ tables and people across the country are gaining interest in local grains, we are understanding the possibilities. If people can spend $30 on a bottle of olive oil, then why not spend $10 on a great loaf of bread?”

There are 183 flour mills in the United States, according to the US Department of Agriculture, and tens of thousands have closed in a century. But now the local food movement and the drive toward sustainable agriculture is attracting new investors to support change in the grain industry. Cairnspring’s key partners include Patagonia’s venture capital fund Tin Shed Ventures, the Port of Skagit, Camas Country Mill and Washington State University’s The Bread Lab, as well as local farmers.

“We process single varietal flours, mostly type 85 (ash content),” says Kevin Morse, chief executive officer of Cairnspring Mills, who spent nearly 10 years as program director and economic development executive for The Nature Conservancy in Seattle. He left in 2015 to become a co-founder of Cairnspring Mills with Tom Hunton, owner of Camas Country Mill, which operates a stone mill in Oregon’s Willamette Valley and focuses on whole grain flours.

“I got to see what happens when local producers leave an area. We lost a lot of farmers,” Morse recalls from his previous career. “Our goal is to help rebuild the local farm community. We pay growers $1.50 to $2 a bushel more than commodity wheat. The bar is defintiely higher, and they have to earn it. We have no false notion that our flour will replace community flour, but we are certainly going to offer a choice and a whole new variety of flours that you can’t find elsewhere. Consumers today are willing to pay for certain attributes. That’s what makes it work.”

DePasquale says his wholesale bakery uses Expresso variety wheat in a new single-origin bread line that includes three products: a miche, baguette and pan bread. “You can identify the flavors. It’s a good wheat,” DePasquale says. “I’ve been playing around with different flavors, wherever I can find heritage wheats. We needed to make this work commercially. We’re a mid-size bakery, so a certain amount of bread has to be pretty consistent. We can’t say to the customer that this will be available when it’s available.”

Speadheading change

Fueled by work from The Bread Lab and others, innovators on the West Coast and in the Pacific Northwest are helping lead the way for how specialty wheats are grown and freshly milled into flour at local or regional mills.

Nicky Giusto of Central Milling, a leading miller of organic and specialty flours based in Logan, Utah, explains that milling in-house can create two very difficult horses to tame: flour consistency and grain quality. Many bakers that he sees milling in-house tend to blend flour from a mill with their local product to make their in-house milling system work — “not ideal for the baker that has all their chips on the local table,” Giusto says, “but a step in the right direction.”

“Milling in-house makes sense for bakers that do not live near a mill or bakers that are wanting to bake with only the freshest whole grain flour,” he says. “However, they are complicating a profession that is already difficult. It’s not easy to mill flour consistently; the stone mill needs to be watched and the granulation felt often. Even if the baker is successful at milling to a consistent granulation, they may be dealing with local wheat that has its quality fluctuations. Most local farmers are not providing the bakers who are purchasing their grain with an analysis of their grain. The baker will have to spend a lot of time adjusting their mix which can lead to lost product — wasted money.”

Mike Zakowski, owner of The Bejkr in Sonoma, California, agrees that grain quality can vary a lot from season to season, even plot to plot, “as all soils are different and have different needs for replacing nutrients into the soil. For example, if it’s a hard red wheat that is weak or has a low protein that won’t develop into good bread structure, maybe it can be used for sprouting, crackers, dog biscuits and possibly countless other uses.”

Craig Ponsford, baker and instructor at Central Milling’s Artisan Baking Center, says that a one-man show doing in-house milling seems to almost make it look easy, “but as soon as there are other hands involved, then it becomes difficult. The chance of having two master bakers in one location is very unlikely, let alone one. The respect factor — for me — is consistency, and my guess is if you are trying to mill more than 30% of your flour needs then you are having a hard time with consistency. I highly recommend keeping it a small and manageable part of the business.”

At Ibis Bakery in Kansas City, Missouri, where they use an on-site stone mill to produce freshly milled flour, co-owner Chris Matsch says they bolt some flour and that process can get messy. “It makes the cleaning and upkeep of our mill room quite intense. We are installing a large air filtration system in an effort to eliminate a lot of that airborne dust. Humidity and heat both play a huge role here in the Midwest. Both of these variables can create inconsistency issues both in the storage of grain and during the milling process. We have altered our formulas for our production to be more flexible and less rigid. This allows for adjustments in hydration, time, etc., to be made on the fly, depending on the properties of the flour.”

The added variable of freshly milled flour makes the baker’s jobs much more difficult, he admits. He credits his team for being “amazingly flexible and up for the challenge through this time of transitioning” over to an in-house milling program.

Zakowski points out the challenge of milling your own flour in-house is just that — “it’s another craft to tackle. I definitely believe it’s good for a small scale but I’m sure it could be more challenging as you scale up unless you keep someone to be a dedicated miller in house.”

Taylor Petrehn, owner of 1900 Barker in Lawrence, Kansas, found this to be true after he experimented with sourcing local wheat from Moon on the Meadow Farm, which was raising 1 to 10 acres of Turkey Red. The supply proved inconsistent, mainly because of weather. Plus, the challenge of running a small business and managing in-house milling and baking is a lot to tackle.

“It’s going to test the bakers’ skill set. In-house milling takes a lot of time. It would be challenging just finding the time for milling, when you also have a business to run,” says Petrehn, who was nominated as a semifinalist for the 2017 James Beard Award for Outstanding Baker. “Eventually we’d like to mill our own grain. Our milling capacity is so small. Right now, we are exclusively using flour from Central Milling.

“I think the future of this movement is small bakeries having immediate proximity to the mill itself. You really need more understanding than flour coming out of the sack. I want to know the field. More and more small mills are popping up, with more small bakeries that are demanding that grain.”

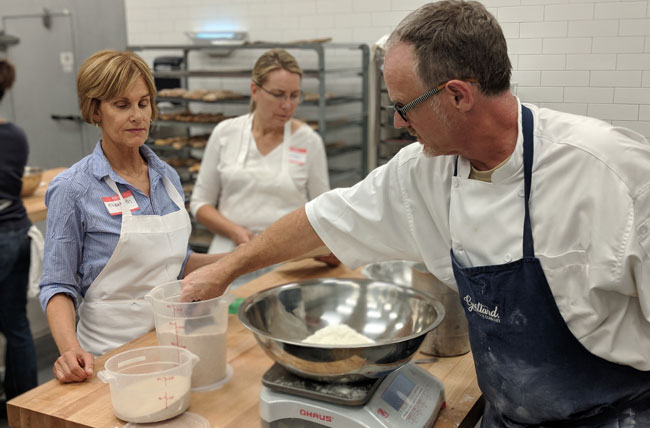

Bellegarde Bakery in New Orleans is a wholesale bakery providing fresh flour and bread to more than 100 restaurants and markets in Louisiana. One of Bellegarde’s head bakers, Morgan Angelle, says they use a 40-inch granite stone mill to mill their flour, producing nearly 5,000 loaves of bread a week. Currently they mill six varieties of grain.

“Being able to do our own milling and baking test is a great advantage to having our own stone mill. I always like to know what is out there and what our most trusted farmers are growing and why,” Angelle says. “Before making a new grain purchase we always mill a sample of the harvest to perform our own test. We do prefer a higher protein flour (12% to 15%), but more important is the quality of the protein.”

Founded in 2013, Manresa Bread has two retail locations in the San Francisco Bay Area and is available at Verve Coffee Roasters locations in Santa Cruz and San Francisco. The bakery produces 3,500 loaves of bread a week, using more than 4,000 pounds of organic flour. About 2,000 pounds of this flour is freshly milled in-house each week. Manresa Bread produces its bread and pastries in a 3,400-square-foot commissary kitchen located down the street from the Los Gatos retail space. Earlier this year, Manresa installed a stone mill to produce freshly milled flours.

“The new mill is something we are learning about,” partner and head baker Avery Ruzicka says. “Now you can put 300 pounds of grain in a hopper at one time, and an hour later (depending on the grain) have 300 pounds of flour. Being an artisan baker, it’s my job to provide the clarity of what the end product should be. With the new mill, we can mill fine flour. We use freshly milled in everything but croissants. Croissants are the next step. The structure will be dictated by the lamination itself. There is not as much room to make edits as in bread making.”

Speaking at the 2017 International Bread Symposium at Johnson & Wales University in Charlotte, North Carolina, Chad Robertson of the acclaimed Tartine Bakery in San Francisco said he’s learned plenty of valuable lessons since working with local and ancient grains for more than a decade.

“I want to get back to using lots of fresh milled stuff. There’s no other way to get that flavor,” Robertson said. “But I have learned that for me to mill everything myself is too much. So why not work with fresh millers nearby?”

Similarly, Scott Fox, vice president of bakery for three-store Dorothy Lane Market in Dayton, Ohio, speaks with great enthusiasm about the Turkey Red variety wheat they use in their bread program at the DLM Bakehouse. They sell a Turkey Red Wheat Bread made from local grain that’s grown 20 miles from one of their supermarkets. Danny Jones, the farmer, grew 50 acres of Turkey Red wheat this year, up from 10 acres a year ago and 2½ acres the first year of the program in 2016.

“The farmer mills it fresh for us and delivers fresh flour two or three times a week,” Fox said in July. “They just harvested this year’s crop last week, and yield was up from 35 bushels to 45 bushels per acre. The protein levels were over 14 percent, which is amazing from wheat grown in this area.”

Dorothy Lane Market has partnered with local farmers Ed Hill, Dale Friesen and Jones to grow the wheat, which has been a great source of pride. Skilled DLM artisan bread bakers work it into dough and bake this Turkey Red Wheat Bread on a European hearth oven for a one-of-a-kind flavor, available while supplies last each year. “It has a sweet, nutty flavor,” Fox says. “Our head baker uses it to make a poolish for a French style bread. We are really inspired by sourdoughs. We have started a sourdough from Turkey Red. We demo it and tell the story of the bread. Our customers love it. For foodies, they enjoy knowing we are using heritage grains and that it’s grown locally. They want to do business with local people.”

Financial implications for local grain

Local grain has another obstacle to overcome: financial incentives. Wesley Fehsenfeld of The Uhlmann Company in Kansas City, Missouri, points out the financial incentives of local grain are derived from scarcity and other characteristics that a niche market would assume — very similar to organic crops. “However, quality crops certainly get rewarded and can stand out from the rest,” he says. “A grain’s story can’t sell itself when its quality is lackluster, and it struggles to perform for a baker.”

“I think for the average farmer, there is not a huge incentive to allocate acres away from traditional crops to heritage crops,” he continues. “It works for small-scale, sustainably minded landowners who are interested in these heritage grains. For most successful farmers, it would be more of an aggravation to grow heritage grains because marketing is not as easy as hauling to your local elevator. There are a lot of end users who are looking for smaller quantities of cleaned grain in totes, but most farmers don’t have the equipment to custom clean, store, pack and ship smaller quantities. This type of infrastructure is lacking.”

Another consideration is that crop rotations are very advantageous to farmers, Fehsenfeld says. Planting a new crop can help to restore advantageous soil qualities. “I am not sure that this is a primary driver of heritage grain acres, but it certainly is a plus. Organic farmers already have to have a rotation in place, and I think it starts to make more sense for organic operations. I know an organic farmer in Illinois who is dabbling in the heritage grains. He has set up a small mill to service bakeries in Chicago. The bulk of his crop is contracted with end users ranging from distilling to baking. This type of arrangement works very well for the farmer. He has the advantage of being relatively close to a large metro like Chicago and also growing contracted crops.”

On the flip side, Fehsenfeld knows of an operation in western Kansas that has done a great deal of work with Turkey Red, “but because they aren’t near a large metro, they don’t compete well. They are planning on diversifying considerably because Turkey Red has quickly become so popular that most end users can find a closer source. In summary, heritage grains can easily fetch a premium if the quality is good. The lack of infrastructure hurts the growth of these grains but also leads to the scarcity that makes them more interesting. We are sure to see an increase in acres to these crops but not from successful large-scale farms, primarily from smaller to mid-size farms who are winding down or are interested in pursuing something a little more exciting.”

Robert Morando, president of Farmer Direct Foods in New Cambria, Kansas, points out that for regional wheat farmers looking to appeal to artisan craft bakers, “they’re going for quality over quantity.” A farmer-owned cooperative, Farmers Direct Foods manufactures “All Natural” Whole White and Red Stone Ground wheat flours, which contain 100% of all the nutritional value with no added enrichments and also no preservatives.

Farmer Direct wheat is grown using sustainable farming practices utilizing specific certified varieties of wheat with superior baking performance. This wheat is also trademarked as “IA - Identity Assured,” meaning that from planting through harvest, then onward through the milling process, Farmer Direct tracks each individual lot right into the packages that they sell with 100% traceability.

The road ahead

The farmer, baker, miller partnership is integral to success at Central Milling, which has been in continuous operation since 1867. “Central Milling is quite successful because we live by the farmer, miller, baker model rigorously,” Giusto says. “We believe that one cannot exist without the other. In short, we listen to the baker’s wants and needs.”

As for the future of heritage, single-variety grains, he adds, “They look nice on a bakery menu. You sound cool talking to a fellow baker, chef, or interested foodie. To me, it’s not sustainable. It can hurt the farmer and can lead to a situation where you’ll be in conflict with your local claim. Let me explain. Heritage is defined by a year range. I’m not sure what this range is exactly, but let’s say it’s 50 years. So, wheat in rotation 50 years ago is somehow superior to varieties bred and put into production 40 years ago. What we are saying is in 10 years it will be OK for me to use the newer variety and call it heritage. It doesn’t make sense to me.”

Dave Green, executive vice president of the Wheat Quality Council, agrees. “There is a reason these varieties aren’t grown now, and it typically has to do with disease resistance.”

Using a heritage variety of wheat in your bakery because it sounds more authentic without knowing how it affected the farmer is not sustainable, Giusto says. There are a few main reasons wheat breeders do what they do: increase yield for farmers, protect farmers from crop loss because of plant disease (breed for resistance), and to keep the flavor, color, and baking characteristics of a certain variety intact.

That’s where modern varieties of local wheats come into play. Modern wheats can be bred with heritage varieties to develop stronger and more flavorful wheats. Many bakers and breeders expect a steady increase in growth ahead for modern wheat varieties, which are becoming available in greater supplies.

As the industry moves forward, another significant goal of bakers like DePasquale of Essential Baking Company and Matsch of Ibis Bakery is to develop a consumer following for a distinguishable regional flavor profile of bread. San Francisco has its sourdough. What might the Pacific Northwest or Kansas City offer?

“If you take a look a Europe, for example, the countries there all have their own history and versions of bread based on the grain that is grown in that region,” Matsch says. “They also have wines produced in the same way: lots of little regions interpreting their wine in connection to the local ecosystem.

“I’m passionate about this concept because of the impact it has on the local grain supply chain. Using locally grown grain eliminates some of the mass transit that happens in the commodity grain market. If the baker has a mill in-house, it also eliminates the need for mass-milled grain into flour.

“The direct communication between the farmer and baker can increase quality year over year; new wheat can be grown, and new products can be tested. We have been fortunate enough to have several farms work with us to plant heritage grains around Kansas City. Other farmers are now interested in growing heritage wheat. Restaurants, individuals, and other bakeries are also interested in purchasing these grains.”